Today would have been my paternal grandfather’s 100th birthday. When I wrote about my maternal grandfather’s century a few years ago, I decided at the time that it wouldn’t be a one-off, that I would write about all four of my grandparents on the day they would have turned 100. So here we are, nine days after I turned 51.

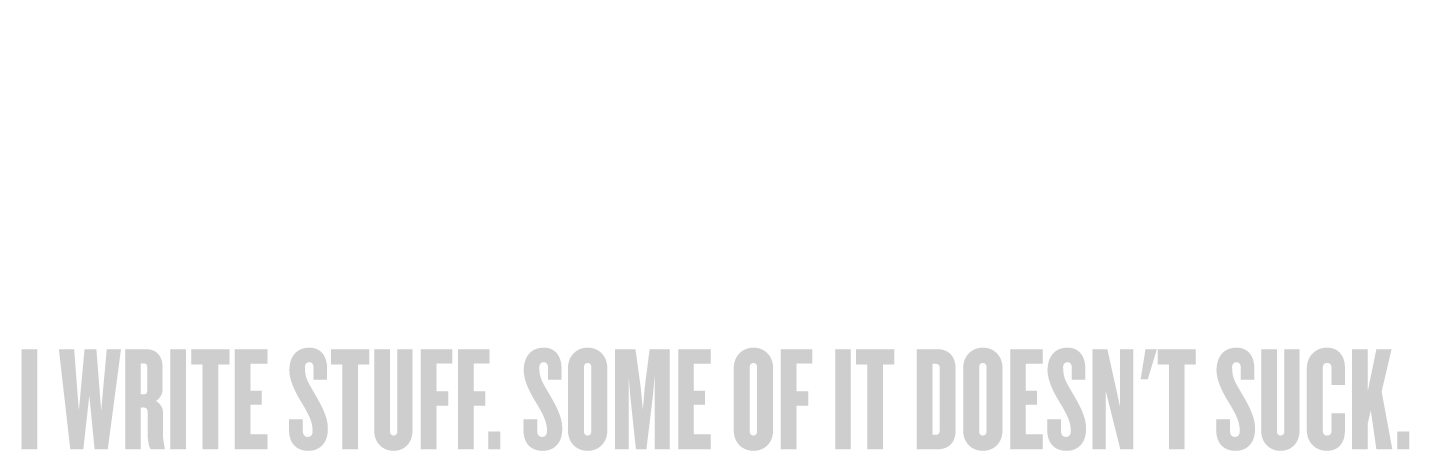

That picture up there is my grandfather as an “early adult.” Other than that text on the file, I have no idea when it was taken or how old he was, but I like that picture a lot. I like his smile. And you know how the past hits us — he could be sixteen in that photo, or he could be 26. No way to know.

My grandfather was 48 years old when I was born, which means that he would have been my current age at around the time I became aware of him. That…messes with me. Because by the time he was my age, my grandfather had raised two sons to adulthood and founded — and run — a number of successful businesses.

Me? I have kids in elementary school and have amassed a depressingly impressive number of comic books and Flash toys.

It’s a different time, of course, and I don’t actually compare myself to my grandfather on a regular basis. I do occasionally wonder, though, if his entrepreneurial spirit and restless drive were passed down to me in the form of a brain that just can’t stop creating, even at those times when the things it creates are useless or pointless or risible.

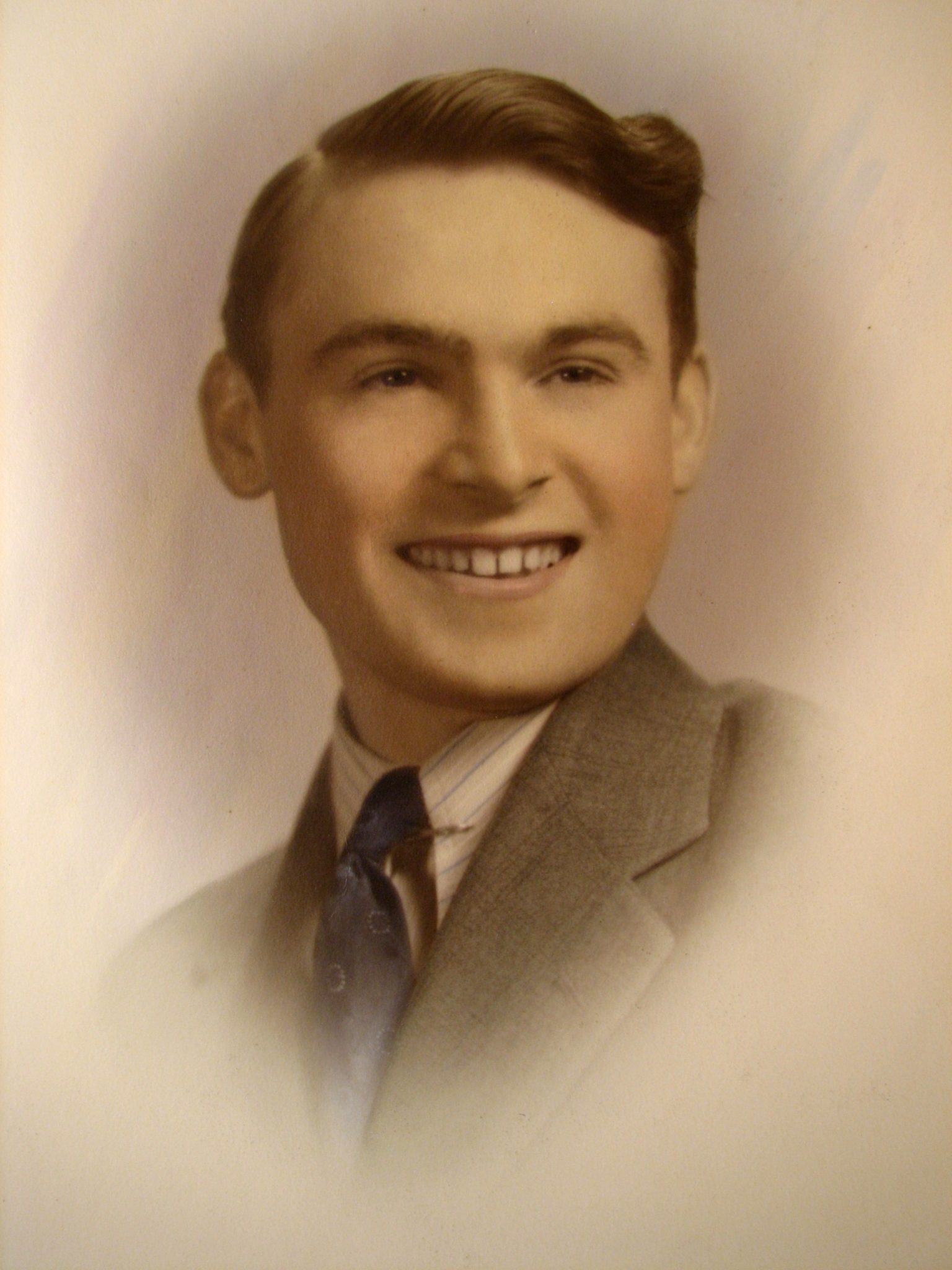

When I was a kid, my grandfather owned and ran a metal shop that he’d founded decades past. Here’s a picture of him in his high school yearbook in 1941:

Prime age to be drafted into World War II, right? Wrong. The government figured he was worth more to them running the metal shop, churning out parts for the war effort. (There isn’t much of a history of military service in my family, and I’m not sure how I feel about that, honestly.)

(BTW, I love the guy below him, Douglas, whose nickname of “Doug” had to be spelled out. Ah, 1941! He also looks a little bit like Agent Smith, doesn’t he? Oh, damn — have we been in the Matrix all this time?)

Anyway, Grandpa ran the metal shop, which I remember fondly because it was the seventies, but the place was computerized and had these massive printers that used gigantic sheets of paper, like this:

My grandparents would give me that stuff all day long, and I’d flip it over to the blank side and draw comic books until my pencils died.

(And yeah, Grandma helped run the factory, but we’ll get to her in about five years.)

My grandparents lived in an old house a stone’s throw from the shop. They walked less than five minutes to work each day. Eventually, they sold the shop and the house and built a frankly ridiculous mansion-y thing in another part of town. I don’t think I knew my grandparents “had money” until they built that house. By then, they were in their late fifties and I think they just figured they deserved a nice house.

The problem with writing about my grandfather is that there are million things to talk about. He was accomplished. He started and ran the metal shop. He financed and built entire housing developments. He was part-owner of a bank.

But that’s the stuff of obituaries, and this isn’t an obit.

What he really wanted in life was to be a farmer. He grew blueberries, lemons, and figs in the backyard, kept a greenhouse attached to his house, and then went full farmer when he decided not to sell a parcel of land he had. Instead, he rented it out with the proviso that he could use a section of the acreage to grow the stuff my grandmother wouldn’t let him steal backyard space for.

He also made his own wine. I was too young to try it, but I am reliably informed by my father that “King William” was absolutely terrible.

He was, I think, baffled by my choice of career. Mostly, I imagine, because he built things. And with a book, well, yes, there’s a book, but… Books are ephemeral, after all. I proudly sent him my first published novel, and then made the entire family swear an oath that they would never, ever tell him about Boy Toy.

Because he was old school. Hardcore Eastern Orthodox Catholic. Never heard a swear word come out of his mouth unless he was quoting someone, and even then I could see the pain in his eyes. He once told me that a friend of his had picked up my book from his coffee table, flipped through it, and then said, “Oh, Bill. I can’t read this book.”

She’d stumbled upon the word bullshit.

Grandpa gently suggested that if I moderate my language, I might not lose that reader. I replied that my books were written for today’s teens, not people who’d voted for Eisenhower.

He laughed, and allowed as how I might be right on that score.

Until I was about 15, my grandfather greeted me with a hug and a kiss, and said goodbye in the same way. Then that stopped — I went in for a hug and he kept his arms by his side, then, after a moment of reflection, offered his hand. We shook, like gentlemen.

Our greetings and farewells went on like this until I was somewhere in my late twenties, when suddenly he began to hug me fiercely, often weeping when it was time for us to part.

I got it immediately, even as a kid — my grandfather was Old World, old school. Men did not hug and kiss. Men shook hands. And as I progressed through teendom, I became more a man than not. It was fine. It never bothered me; I never saw it as a rejection or a withholding of affection because I knew he loved me and because I understood. I didn’t agree, but I understood, without words.

But then, suddenly, men did hug. My grandfather was getting older. Sentimental. It’s a cliché that this happens to men as they age, but most clichés have a grounding in reality. And I’ve inherited this sentimentality. If you ever want to see me cry, just run a video of a dad telling his son how much he loves him, and I will suddenly discover that the pollen is so bad today.

I learned from this behavior of his that it was OK to think something…and then realize maybe you were wrong and adjust your behavior accordingly. I think a lot of men out there (women, too, of course, but men in particular) get locked into a certain mode of behavior and then don’t know how to get out.1 And the thing is, it’s so easy — almost effortless — to get out. You just do it. You just make the choice and you hug your damn grandson.

Here’s a funny little anecdote: He didn’t know anything about Superman! I learned this in college, when I was spending a weekend with my grandparents (they were about an hour away from New Haven, so I visited when I could) and they invited friends over for dinner. Somehow the topic turned to movies and one of the friends began explaining Superman: The Movie to my grandfather.

“…and then this guy, this scientist, Bill, he puts the baby in a rocketship, see?”

I can still see it and hear it. My grandfather was nodding along. And of course he didn’t know jack about Superman — he was in high school when Action Comics #1 came out! He wasn’t scoping out the newsstands for comics in 1938!

But it blew my mind because Superman is so important to me and I’d just assumed everyone knew the origin. And my grandfather could not have cared less about Superman, but he sat there and politely listened and absorbed everything his friend told him.

I’m glad he lived to see me make my dreams come true because I think he worried about the life I would lead as a writer. And I’m even more glad that he lived to see me on the New York Times bestsellers list because even though I’d been making my living as a writer for years before that, I think that was a marker he understood. I think at that point, he could finally relax and say, “It’s OK. My grandson will be OK.”

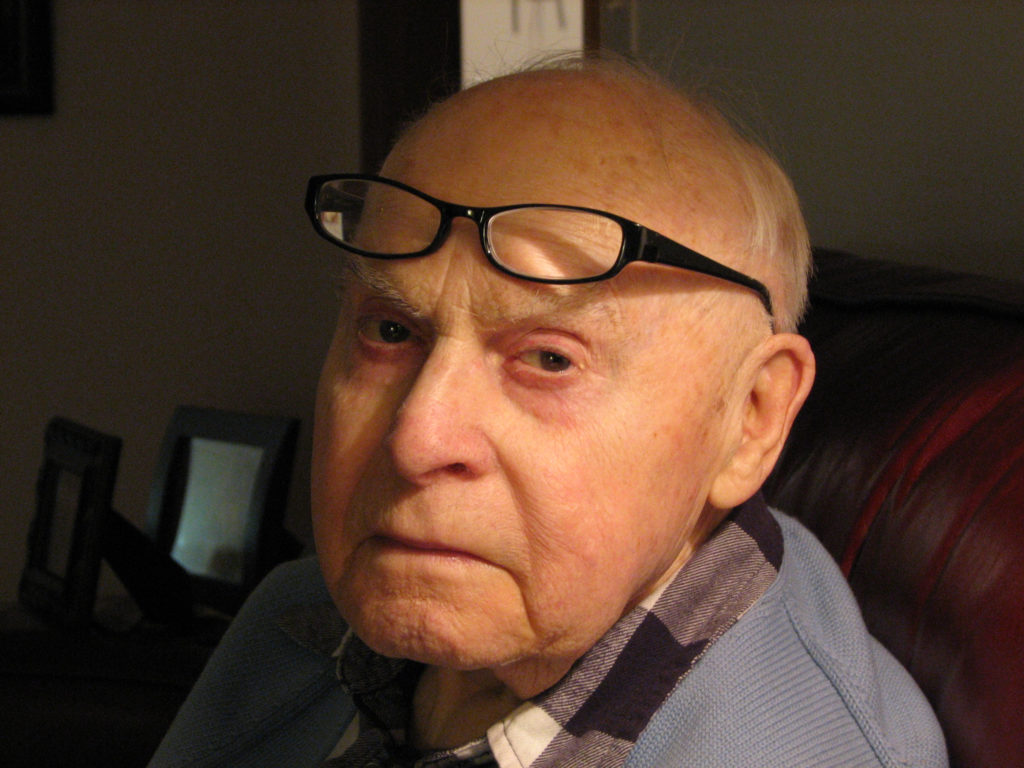

Here’s a picture of him the year he died. I am obviously unable to be objective at all, but I think he looks good for ninety. I hope I do at that age, too.

There’s a lot more to say, but this isn’t a biography of Bill Lyga. This is just to say that damn do I miss him and sorry for swearing, Grandpa, but if you’re ghosting around me, you know I drop worse than that twenty times a day, without even thinking about it.

I don’t believe in heaven, but I also think anything is possible. And I know this: When Bill Lyga passed away, if he found out there was no afterlife, he for damn sure got to work building one.

I enjoyed reading your remembrance of your grandfather. Coincidentally, today would have been my grandfather’s 136th birthday. To put that in perspective, I’m almost 64. He didn’t marry until he was 47 and he was in his early 50s when my mother was born, which explains the wide age difference between me and him. I have little memories of him, as he died when I was four.

Thanks so much for your comment!